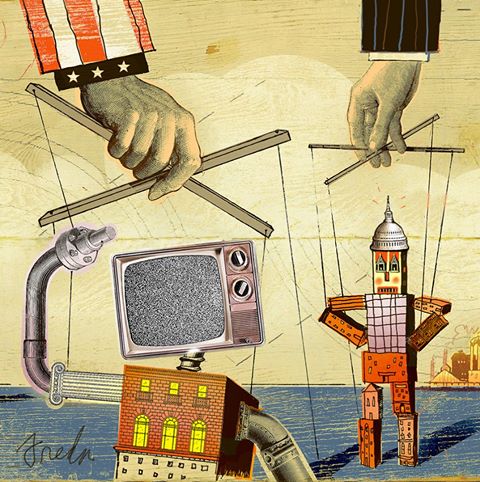

The modern age of mass communication brings us many messages that improve our lives, but we must arm ourselves with the knowledge of its power to influence, lull, suppress, or deceive through techniques that affect a spectrum of human emotion. There is an obscured and often unnoticed tendency towards information manipulation in our complex media environment, undertaken by politicians, government entities, and corporations alike, to shape desired social outcomes—such as the U.S. led ideological War on Terror and subsequent ground wars in the Middle East, among an infinite range of socio-historic events. This critical exploration focuses on how past mechanisms of censorship and information manipulation/propaganda have been cleverly adapted through the ages as a tool of influence (or compliance) to now take advantage of modern mass communication in attempts to sway the minds of the masses.

Historic Censorship in Human Relationships

The Evolution of Influence

Modern Manipulation

InformatIOn Supremacy

The Plot Ever Thickens – The Future Information Wars

Historic Censorship in Human Relationships

As a species that relies heavily on interpersonal communication to survive and propagate, it seems intuitive that a power struggle between competing ideas (values) will result in some ideas not only being rejected, but actively targeted for annihilation. Censorship, in simplified modern terms, is a suppression of “objectionable” communication (Merriam Webster). Of course, the loaded gun in this abridged definition is the term objectionable, which merely hints at the host of perceptual, values based, self-interest focused (etc.) judgments that necessarily vary and at times conflict amongst individuals and their proscribed cultures and ideologies. It is no curious coincidence then, that censorship and information manipulation traces far back in human history—farther back than clichéd references to Gutenberg’s printing press. Activities ranged from the active destruction of information, the prevention of idea conveyance employed strategically to promote desired social objectives, the targeted suppression of an individual to promote conformity to a group, or even the logical utilization of self-censorship to ensure social survivability. Reflecting critically on the historic mechanisms and motivations of censorship can reveal meaningful insight on how this tool of influence has been adapted through time for modern communities, and what its use conveys about the values and nature of a suppressor.

When looking to noted historic examples, censorship frequently appears in its most brutal form under the dictatorial and hegemonic rule of one select group or individual over another, during periods of heightened social tension or uncertainty, or even when deemed simply a matter of survival for a community. Going all the way back to 221 B.C. during the Ch’in Dynasty, feudal China was united (an event which continues to influence present global affairs) with the aid of powerfully influential censorship practices utilized by Emperor Ch’in Shihuang Di (actual names and times may vary according to varied references on the subjects). The emperor’s central government, which became the foundation for over the next 2,000 years of collectivistic Chinese society and culture, was highly focused on standardization and social conformity for efficiency amidst many ideologically disparate groups hostile to a new thought regime (Caso, 2008). The legal codes established amongst subsequent dynasties to maintain effective rule contained provisions for government censorship practices, and an ingrained self-censorship cultural value developed in Chinese society (Caso, 2008). Emperor Ch’in is reported to have silenced opposition and criticisms by ordering dissenters—including Confucian scholars—executed, the banishment of kings, sacred and philosophical text destroyed, and other harsh censorship practices throughout his efficiency focused bureaucracy (Caso, 2008). As a testament to its effectiveness, censorship continues to be relied on by the Chinese government to promote social stability, and is popularly defended as a necessary function of regulating accepted communication amongst the large Chinese collective.

As methods of communicating ideas have increased in means of conveyance (from motion -> touch -> sounds -> words -> speech -> symbols -> pictures -> art -> music -> literature -> technology -> ?), the mechanisms of suppression in corollary have also expanded. The World War II era of censorship exploitation provides a salient illustration of this effect. Adolf Hitler utilized a host of techniques to suppress opposition, from historically unoriginal (yet so often utilized) methods of intimidating or killing his perceived opponents, to replacing or destroying objectionable—Nazi ’s referred to it as “degenerate”—art and literature in society. He also had a host of new mechanisms of mass communication at his disposal to minimize resistance to his regime once in power. The persuasive triad of print, radio, and film communication was strictly monitored, altered, and employed in state sponsored propaganda to pressure the German public (and adversaries outside Germany) against opposition to Nazi Fascism—such instances are meticulously detailed in the public opinion, or “morale”, reports of the Nazi party (Unger, 1966). Mechanisms of censorship to ensure social compliance ranged from close scrutiny and intimidation of individuals to achieve compliance, mass propaganda campaigns to inundate the public with Nazi ideals, the strict regulation of all communication channels including publications, presentations, art, broadcasts, and other popular outlets, with the utilization of coercive intimidation, imprisonment, or even execution for those in disfavor with the party ideologues (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum). This concerted and deliberate effort to manipulate the beliefs and actions of society is revealed in the words of Hermann Goering, one of Hitler’s top aids, before being sentenced to death at Nuremberg, “The people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders…All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the peacemakers for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country” (Aronson, 2007). The social values underpinning this form of censorship became undeniable with the discovery of concentration camps and admissions of Nazi party officials in the aftermath of the war: commitment to the state and its socially volatile ideology was shown to be above all reproach from humanity, science, or reason.

Even before this critical WWII era, public relations pioneer Edward Bernays was working on adapting and initiating new propaganda techniques for peacetime, in order to sway the American consumer masses. He was instrumental in popularizing the notion that mass communications could be used as a tool of social influence to manipulate people’s emotions or attitudes and direct changes in beliefs and actions (Dumcombe, 1999). In 1947, Bernays drafted an article he entitled, “The Engineering of Consent,” where he outlined specific actions that could be taken to subtly, yet effectively exert influence on peoples attitudes and behaviors. In order to achieve his objectives, Bernays studied his environment, understood the importance of timing, and was able to engineer news worthy events that could spread hastily across communication channels. His direct manipulation of the media environment resulted in many profound changes in American culture, such as the adoption of bacon and eggs for breakfast with the underlying goal of increasing profits for clients in the farming industry; his Torches of Freedom publicity stunt leveraged woman’s rights sentiment in order to sell cigarettes to women (at a time when this was considered socially unacceptable); and he also helped introduce the deluge of public relation firms that help shape public perceptions of powerful government and corporate clients to this very day (Dumcombe, 1999). His espousal of the notion that “freedom of speech and its democratic corollary, a free press, have tacitly expanded our Bill of Rights to include the right of persuasion” was remarkably effective at laying the very foundation of Colbert’s “truthiness” (Burnays, 1947). In one of his many available publications on social influence, Burnays asserts: “When the public is convinced of the soundness of an idea, it will proceed to action. People translate an idea into action suggested by the idea itself, whether it is ideological, political, or social. They may adopt a philosophy that stresses racial and religious tolerance; they may vote a New Deal into office; or they may organize a consumers’ buying strike. But such results do not just happen. In a democracy they can be accomplished principally by the engineering of consent” (Bernays, 1947). Bernays is ultimately credited with crafting a modern framework for harnessing mass media and communication outlets that can work on an emotional and psychological level, to achieve targeted outcomes without arousing public suspicion of manipulation.

Today, societies deal with even more pervasive and complex mechanisms of mass media influence that, given historic circumstances, require careful scrutiny to distinguish manipulative tendencies that can affect attitudes and decisions. Although the trend of violent forms suppression and censorship has lessoned in progression with modern means of mass communication (with the ability to bring quick attention to horrendous human rights violations), notable recent exceptions, like the violent quelling of Tiananmen Square pro-democracy demonstrations in China (1989) and similar free speech riots around the world, can likely be expected to continue into the foreseeable future –particularly when ideas are deemed harmful to the interests of those in positions of leadership, authority, or persuasive communications. Yet, historic censorship and propaganda techniques have been much refined even since Ed Bernays profiteered from his tremendous insights on media manipulation, becoming a multi-millionaire by the end of his long career and imbedding him-self in popular culture as the “Father of Spin” (Tye, 1999).

When looking to salient illustrations of mass media manipulation in the post 9/11 era, the media savvy communicator must be willing to take an even wider view on mechanisms of influence. With the messages of influence in the U.S., where freedom of information is a benchmark moniker of the dominant rhetoric, the reality and intentions behind the headlines may be much more obscure. Working with the Department of Defense exposed me to the shadowy world of Information Operations, openly defined as “the integrated employment of the core capabilities of electronic warfare, computer network operations, psychological operations, military deception and operations security, in concert with specified supporting and related capabilities, to influence, disrupt, corrupt or usurp adversarial human and automated decision making while protecting our own” (Joint Publication 3-13, 2006). This is a highly complex communications environment where the U.S. Department of Defense and affiliates actively work to influence even the machines or networks that subsequently influence people. These concepts share many congruencies with Bernays methods of influence, such as the chief objective of influencing decisions or behaviors of targeted adversaries, groups, social leaders, or other information sources, including public and private media organizations around the world.

While this type of doctrinal policy of information supremacy and manipulation for desired outcomes was in place long before the attacks on September 11th, there have been noteworthy assertions and indications that such mechanisms of influence were subtly employed to shift attitudes of Americans, including in the path to war in Iraq, as well as the War on Terrorism. The Redon Group (TRG), is a 21st century PR and consulting firm (authorized by DoD entities to research and analyze information at the highest levels of classification). It has been criticized for taking part in shaping the media atmosphere around the world (for several decades). In a speech to the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1996, John Rendon (founder of the Rendon Group) explains his motivating philosophy to a group of graduating cadets, “I am not a national-security strategist or a military tactician…I am a politician, a person who uses communication to meet public-policy or corporate-policy objectives” (Bamford, 2005). Investigative reporting by J. Bamford, with Rolling Stone magazine (one of many such reports circulating the inter-webs) notes some interesting linkages between TRG and the type of mass influence strategies that have been discussed in this critical essay. A quick visit to TRG’s website reveals they tout themselves as a premiere provider of information influence, declaring prominently that, “for three decades in 97 countries, TRG has been known as a leader in a diverse number of specialized services that are utilized by the world’s most powerful corporations and governments…we have planned and executed complex, global, multi-channel campaigns for dozens of clients…our body of experiential knowledge is based on nearly three decades of executing communications programs, informed by research into new innovations at the edge of the influence spectrum” (The Rendon Group, 2011). According to Bamford’s investigation, “three weeks after the September 11th attacks…the Pentagon awarded a large contract to the Rendon Group” and “around the same time, Pentagon officials also set up a highly secret organization called the Office of Strategic Influence…[with the mission] to conduct covert disinformation and deception operations (Bamford, 2005).

Bamford asserts “the contract called for the Rendon Group to undertake a massive ‘media mapping’ campaign against the news organization, which the Pentagon considered critical to U.S. objectives in the War on Terrorism,” and was understood to be “deploying teams of information warriors to allied nations to assist them ‘in developing and delivering specific messages to the local population, combatants, frontline states, the media and the international community’” (Bamford, 2005). Yet another area linking the influence of Rendon is his reported advising role as a part of the Second Bush White House’s Office of Global Communications, “which was charged with spreading the administration’s message on the War in Iraq” (Bamford, 2005). Are these associations between powerful PR manipulators and government entities part of a vast conspiracy to use mass communication channels to engineer key events for politicians, powerful clients, and businesses, or are theses highly refined mechanism of media influence being used to justly convey truth to the masses? Or simply a natural phenomenon of an evolving communication landscape? Possibly a combination of some, all, and none.

The Plot Ever Thickens: The Future Information Wars

Looking back in History at censorship provides many clues as to how this influential communications regulator has influenced cultures both past and present. As civilizations have advanced, censorship practices have evolved along side new forms of communion purveyance, revealing the integral link between information conveyance, suppression, and manipulation. In modern cultures informed by internet web searches and entertainment T.V., it can be difficult to recognize what messages are being suppressed/censored and what values are being promoted. By looking closely at the mechanisms and motivations of censorship through time—from classic book burning, the WWII Nazi propaganda machine, to modern mass media environments—it becomes much easier to identify the complex way forms of censorship continue to be utilized to influence social outcomes around the globe. Current popular media outlets are both active and passive censors, which we rely on to deliver inter-community information for what essentially amounts to our survival. In order to be tools for effective social improvement (if that is what these entities are to be used for), mass communication outlets should place considerable emphasis on messages that include the perspective of multiple well considered sources, that conduct analysis and problem solving, and that promote sustainability and the environment, while also becoming accessible and relevant to society. The development and current systematic use of mass-media communication and advertising by U.S. politicians, government entities, and corporations alike, asserts a dominant form of rhetoric that can and has been adapted to influence actions, decisions, and to change cultures. What will the future of Censorship look like? How will our communication landscape continue to change? And what does this mean for our survival, our cultures, and our communities? If you would like to read more about the Art of Information, with some of my own personal accounts of the information landscape, let me know by leaving a comment.

Sources of Attribution:

Aronson, E. (2007). The social animal (10th Ed.), Mass Communication, Propaganda, and Persuasion, New York: Worth.

Bamford, J. (2005). “The man who sold the war”. Rolling Stone, 988, 52-62.

Burnays E. (March, 1947). The Engineering of Consent, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 250: pp. 113-120.

Caso F. (2008), “Censorship”, InfoBase publishing, Facts on File, Inc., pp. 58.

Dumcombe S. (1999), The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations by Larry Tye, Review by: Stephen

Dumcombe, The New England Quarterly , Vol. 72, No. 3 (Sep., 1999), pp. 495-500, http://www.jstor.org/stable/366899.

Joint Publication 3-13, “What are Information Operations?” (2006). U.S. Air Force Air University, retrieved on 2 Dec, 2011 at http://www.au.af.mil/info-ops/what.htm.

The Rendon Group, (2011). Strategic communications. Edge thinking. Company website, Retrieved on 2 Dec, 2011 at http://www.rendon.com/about/.

Tye L. (1998). The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations, Ney York: Crown Publishers, Inc.

Unger A. (1966), “The Public Opinion Reports of the Nazi Party”, American Association for Public Opinion Research, The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 29 No. 4 pp. 565-582.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Nazi Propaganda and Censorship, retrieved on 2 Dec, 2011 at http://www.ushmm.org/outreach/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007677.